git

Access Models

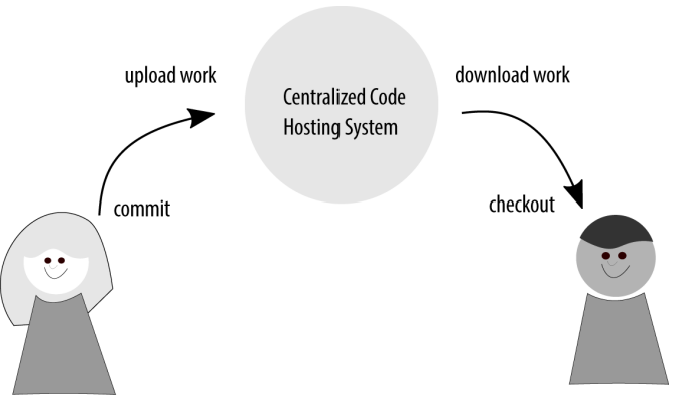

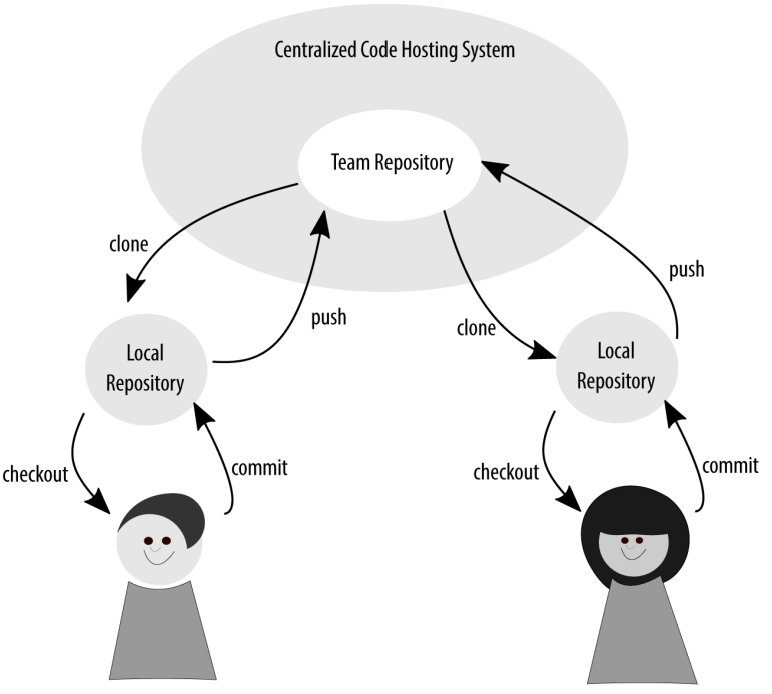

If you have been using version control for a long time, you may remember systems like CVS or Subversion with a centralized repository. demonstrates how changes were made in Subversion’s centralized system. In this system, each time you wanted to save a snapshot of your work to the repository, you were potentially saving to the same place as someone else. Just when you thought you were ready to share your work, or request a code review, you would sometimes be prevented from doing so if someone else had recently updated the same branch with their own work.

Working with files in Subversion

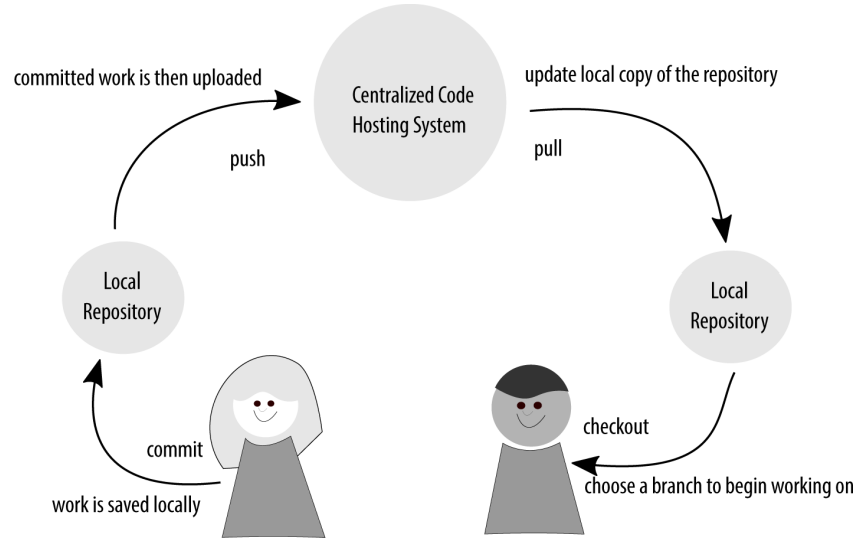

Git, on the other hand, is a distributed version control system. This means instead of having one central place that everyone must use if they want to have their changes recorded, each person works independently from the centralized code hosting system, and is responsible for making commits to his or her local copy of the repository. This means changes from other developers are never forced into your work; instead, it is your decision of when to incorporate outside work, and when to share your own

Every time you sit down to work with Git, you are sort of working in a centralized fashion as far as your computer is concerned; your repository of changes is entirely self-contained on your local machine. You do some work, and then save that work to your local repository. Then, when you’re ready to share your work with others, you make a connection to a remote repository and push your copy of a specific branch to it.

Working with files in Git

Keeping your work entirely local would be very limiting! Instead, we make connections to other systems, and share our code through the remote repositories.

Git does not have the ability to control access—instead, it allows any developer full read/write access to the repository. At the most coarse level, you limit this control through login controls. I develop on my machine, to which you don’t have access, and therefore you cannot change my repository. As soon as we put the repository in a shared location, such as a centralized code hosting server, we need to agree on how we will govern our access to the repository.

Some Git hosting systems, such as Bitbucket, allow fine-grained, per-branch access controls; however, most force you to limit control on a per-repository basis. In other words, you either are a committer for any branch on the repository, or you are limited to making your contributions through pull requests.

The three most popular models

- Single Repository; Shared Maintenance, wherein everyone on the team is considered a maintainer and is granted access to upload changes to the project repository.

- Collocated Contributor Repositories, wherein contributing developers create a remote copy of a project, and have their changes accepted by project maintainers.

- Dispersed Contributor Repositories, wherein code is shared via a text-based patch file.

Dispersed Contributor Model

When Git was originally conceived, conversations about changes to the code base of an open source software project commonly happened on public mailing lists, not on centralized web hubs. This model is still used today by the Git development team. It is almost certainly not appropriate for your team to use this model for its development;however, understanding the model has implications for some of the more advanced concepts required to use the commands rebase and bisect.

To share their work with the community, developers would create a patch file using the program diff. They would then write an email to the discussion group, and attach their patch file. To investigate the proposed changes, members of the mailing list would download the attached patch file, and apply it to their local code base, using their system’s patch command.

By sharing the patch files via a mailing list, developers were able to encapsulate and share their work-while efficiently limiting what was shared to that patch file so that the people evaluating the work could easily see what had changed between two specific points in time within a shared code base.

This model is still used by the Git project today it is still using a mailing list to share patches, and have conversations about what features should be added to Git and what bugs should be removed.

Although the model might seem archaic, it does have some advantages:

- You don’t need to use a specific version control system locally because the patch file doesn’t require specific version control software to be installed locally.

- Developers can easily review the proposed changes from the comfort of their email application.

- This model encourages whole idea thinking. If you have to email a group of people each time you make a change, you are more likely to ensure everything is right so you can avoid the embarrassment of “just one more thing.”

- Uploading your proposed changes to a system that is not the code hosting system enforces a review procedure among the participants in the software project. In other words, as a developer, I can’t just upload my changes to the main repository; I have to announce my completed work and wait for someone else to merge it in.

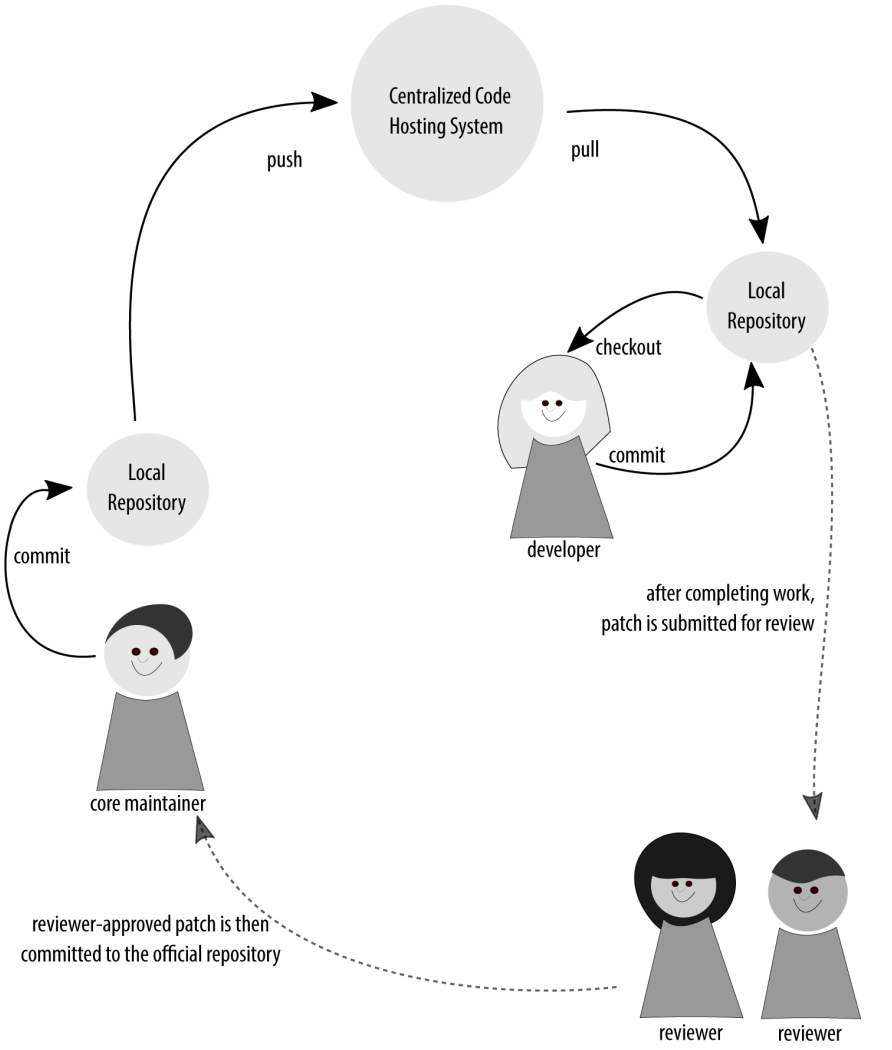

The community review process for patches

Having dispersed repositories isn’t specific to projects that communicate via mailing lists. At the time of this writing, the Drupal project was using a variant of this model. Instead of using a mailing list to share patches, though, it was using a self-hosted,centralized code hosting and ticket issue system.

In this model, you can sign the individual commits before sharing them; however,this makes it more difficult to unpack the history of who made which changes if multiple people were involved. The team will need to, instead, adhere to a patch formatting policy (signed or not), and a commit message style. Drupal has strict formatting guidelines for its commit messages to ensure everyone receives credit for their work.

For most projects starting today, this model is not appropriate. It does, however, help to understand some of the more advanced commands, such as bisect, if you are able to think about commits as whole ideas. A more modern approach to this model is to use fork, or clone, repositories on a single code hosting system.

Collocated Contributor Repositories Model

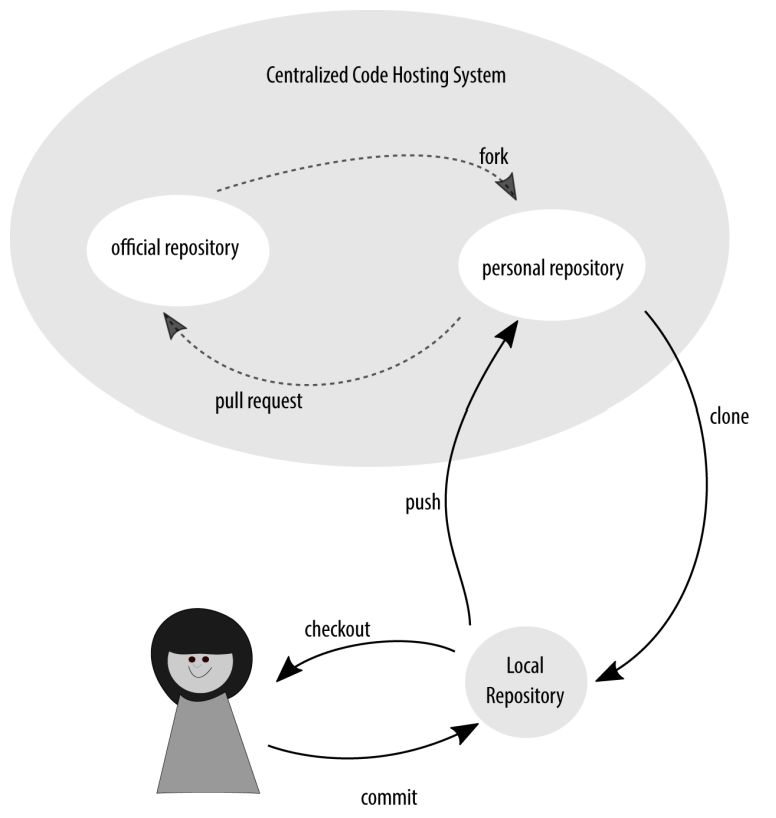

These days, software developers are unlikely to trade patch files instead, they are much more likely to use a central code hosting system that manages the patch process for them. Using a single code hosting system makes it easier to programmatically create and submit patches between repositories. The method for how these patches are managed is the secret sauce that makes up any code hosting system. The restrictions are presumably handled via Git’s pre-commit hooks to ensure access control is respected.

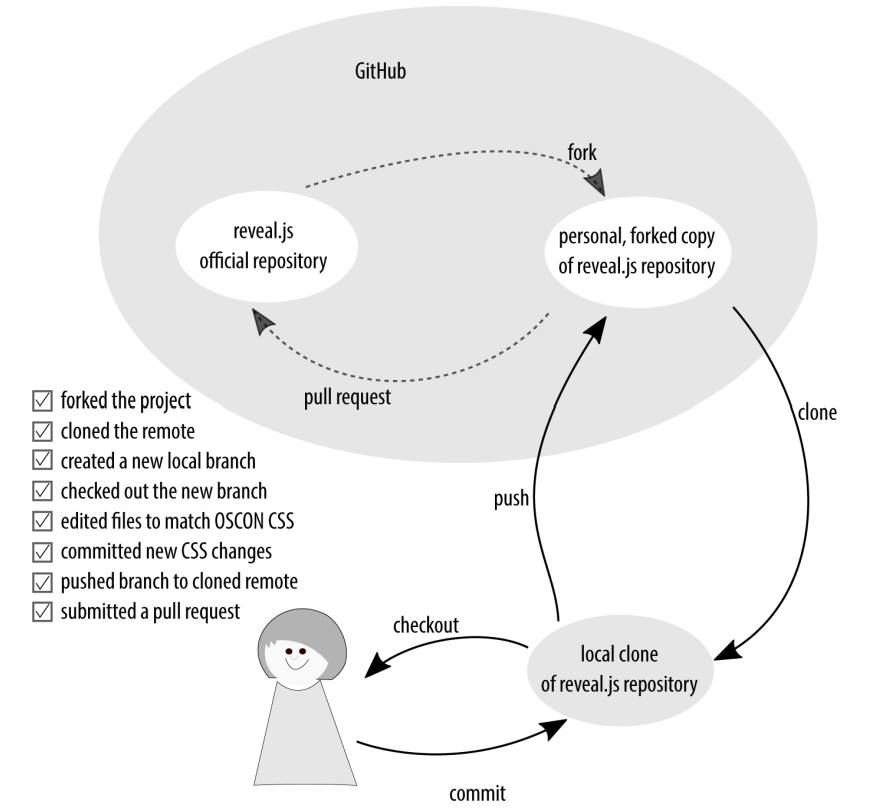

On a collocated system, the “upstream” project retains complete control over who is allowed to write to the primary project repository. Individual contributors make a clone, or fork, of the project to their own repository on the code hosting system. The contributors make changes to the copy, and then submit their requested changes in the form of a merge request or pull request. If you are working on an open source project with a lot of contributors, you are most likely using this model.

Creating a chain of cloned repositories

GitHub has popularized this model for development for contemporary open source projects. I’ve also seen this model used for internal projects with strict walls between departments. For example, if the quality assurance team is solely responsible for the final merging of code into the stable release branch, the team is likely using some variation on this model. Another reason for this separation would be if you were using extra contractors and you wanted to limit their ability to accidentally add something to the repository that hadn’t first undergone a review of some kind.

Shared Maintenance Model

Finally, we have arrived at what is likely the most typical permission model for internal teams (and teams of one): shared maintenance. In this model, there is an inherent trust among team members. It is assumed that code will be checked and verified before it is committed to the main project branch, and that, generally, the developers are trusted. In this model, work is done locally by all developers before it is pushed into the shared repository for the project. When working with an internal team, this is often where we start: with a single shared repository that everyone has shared write access into.

Suggesting changes to a project from collocated repositories

Git does not accommodate permissions and instead relies on other systems to grant or deny write access to a repository. If you do need to prevent people from uploading their code to a shared repository, you need to use the host system’s access control to do so. If you are not using a Git hosting platform, this access control might be controlled via SSH accounts.

Everyone on the team has write access to the central repository from their local repository

Custom Access Models

In addition to these individual strategies, teams may also choose to use multiple access models for a given project. This would be particularly useful for projects with very strict regulations on who could commit code to the canonical repository. Indeed, most open source projects will have different levels of access for different contributors.

A common workflow is as follows:

- An official project repository, to which only a very few people are able to commit code. In an open source project, it would be the project maintainers; and in a closed source, or corporate, project, it could be the quality assurance team.

- A less restricted, internal copy of the repository, which is used for integration by each of the contributors and project teams. This repository might follow a shared maintenance model, where everyone is allowed to merge their branches into the repository as part of a code review process, or even on an ad hoc basis.

- Individually created personal repositories, locked to the individual contributors.These are typically hosted on the same code hosting system as the official repository, because most modern code hosting systems have easy-to-integrate functionality (usually called a “pull request” or “merge request”).

This split would commonly be seen in teams that employ junior developers, quality assurance teams, or perhaps external contractors.